Remembrance Through Art

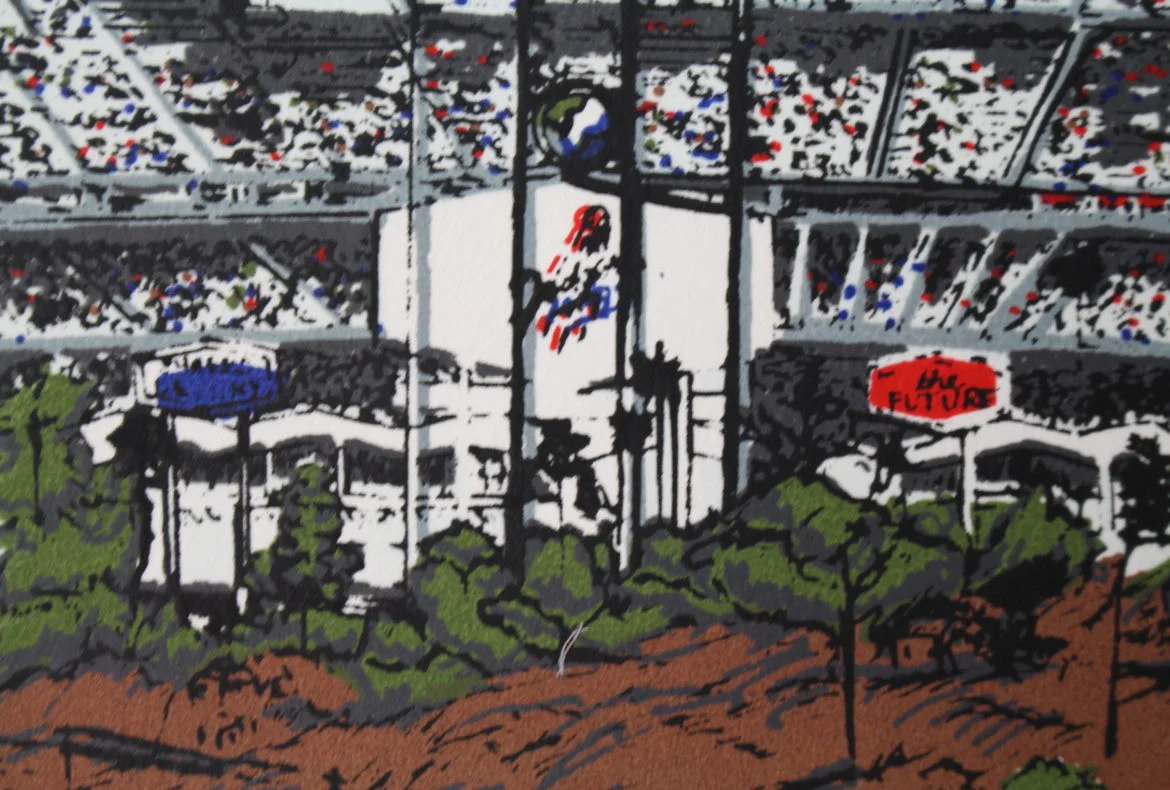

Chavez Ravine by Miyo Stevens-Gandara, 2016

The Dodgers.

Whether or not you’re a baseball fan or from Los Angeles, the Dodgers are a household name. When most people think of the Dodgers, they imagine a full stadium, bright lights, Doyer dogs, the roar of a passionate crowd, and 4th of July-like fireworks. Others look past all of that and remember the people of Chavez Ravine and the independent barrios that made up the area, including La Loma, Palo Verde and Bishop.

Located a few miles from downtown Los Angeles, Chavez Ravine was home to generations of Mexican-Americans. The existence of this self-sufficient town came under attack in 1949 when the Los Angeles City Housing Authority marked Chavez Ravine as a prime location for redevelopment. The town was set out to become “Elysian Park Heights”, but due to the political climate of the 1950s, corporations killed the housing plans by labeling them a socialist plot. After Norris Poulson bought Chavez Ravine at a fraction of the price, city officials persuaded Walter O’Malley to relocate the Brooklyn Dodgers to Los Angeles. Ultimately the remaining residents of Chavez Ravine who had resisted selling their properties were forced out through the burning and demolition of their homes.

Some who remember Chavez Ravine and the story of families being displaced to make space for the stadium, are keeping that history alive and in conversation, such as Los Angeles based artist, Miyo Stevens-Gandara. Stevens-Gandara is drawing parallels between the historical accounts of the Chavez Ravine displacement from the past, with the present issue of gentrification and displacement facing communities, such as Boyle Heights. In her print, “Chavez Ravine”, she captures the history of the Dodger Stadium. “I’m not a huge baseball fan but I always wondered about that [Chavez Ravine] story, that landscape, that narrative. Every time I heard them talk about Chavez Ravine or a Dodger game or something, that had such weight to me, that name, that I always thought of the story. I wanted to create something that reminded us of displacement because it’s happening all over LA. So I thought I’d take something that everybody really loves, like the Dodgers; and use that as an entry point to talk about the history of that area, what happened, and how we shouldn’t do that [displace people] anymore,” says Miyo.

For Miyo, landscapes tell stories about our society, our [individual and collective] priorities, and injustices; and the better we understand our landscapes and the stories that they hold, the better we can protect our environment, which in turn leads to the protection and respect of the people. When asked about the role and responsibility that artists play in LA’s changing neighborhoods due to gentrification and displacement, Stevens-Gandara shared, “I think that our job as artists is to raise awareness on subjects, to point the finger at something and say ‘Hey, look at this!’ or ‘Don’t forget about this!’. The other thing that’s really important to me as an artist is that we should take care of our environment. I don’t know much about nature so through my work I try to educate myself about sustainability and try to reconnect as much as I can because I grew up in an apartment so I didn’t have a backyard or anything like that. I think that’s where it comes from.”

From the artists perspective, art isn’t a vaccine. It isn’t going to solve all of the problems plaguing the city. It’s a tool that like anything else has positive and negative effects. What art has the ability to do is sensorially stimulate people to start a conversation or activate on a call to action for social change.

History has a way of repeating itself. The same issues that the Latinx/ Mexican-American community were facing in the 1950s are the same issues that they’re facing now. Even though textbooks have a way of erasing and omitting vital pieces of history, landscapes hold the stories that often go untold or become forgotten. The only way to learn and to prevent history from repeating itself is to remember, talk, and write about our own history. The key is in slowing down, looking past the surface, and observing.

Miyo Stevens-Gandara is a Los Angeles based artist working with a variety of mediums such as photography, drawing, embroidery, and printmaking. Stevens-Gandara’s art explores issues of identity, culture, environmental degradation, and feminism. Her print “Chavez Ravine” will be on display and for sale at Self Help Graphics’ Annual Print Fair & Exhibition on June 24th. To view more of her work visit miyofineart.com.

Arleny Vargas is a Boyle Heights-bred resident who divides her time between Boston and Los Angeles. She’s currently an undergraduate at Wellesley College pursuing her degree in Spanish and Studio Art. Passionate about art and representation, she seeks to combine her writing and art in an effort to combat negative media representation and amplify the narratives and experiences of the Latinx community.