Agency, Accessibility, and Abolition– Exploring Reproductive Justice in Art

By Starlina Sanchez

Find them online at https://www.sistersong.net/ or Instagram: @sistersong_woc.

SisterSong Women of Color Reproductive Justice Collective was founded in the late nineties by sixteen Black, Indigenous, Latina, and Asian American women-led organizations in the South. They advocate nationally for reproductive justice; defining reproductive justice as “the human right to maintain personal bodily autonomy, have children, not have children, and parent the children we have in safe and sustainable communities”. Bodily autonomy does not solely pertain to personal choice, it is about self-agency and accessibility.

I felt drawn to the topic of “reproductive justice” and the ongoing conversations surrounding the overturning of Roe v. Wade. Both mainstream media and activist perspectives surrounding the topic of reproductive justice felt overwhelmingly narrow due to their exclusion of lived experiences outside the scope of cisgender, middle class white women. The definition of reproductive justice is often presented in an almost identical way to reproductive rights, neglecting how the two differ in meaning with justice extending far beyond abortion. The following serigraph prints created by four women of color artists at Self Help Graphics demonstrate how reproductive justice expands to include individuals who long to be parents and safely sustain not only the wellbeing of their children, but also their communities.

Nacimiento (2004), Mita Cuaron:.

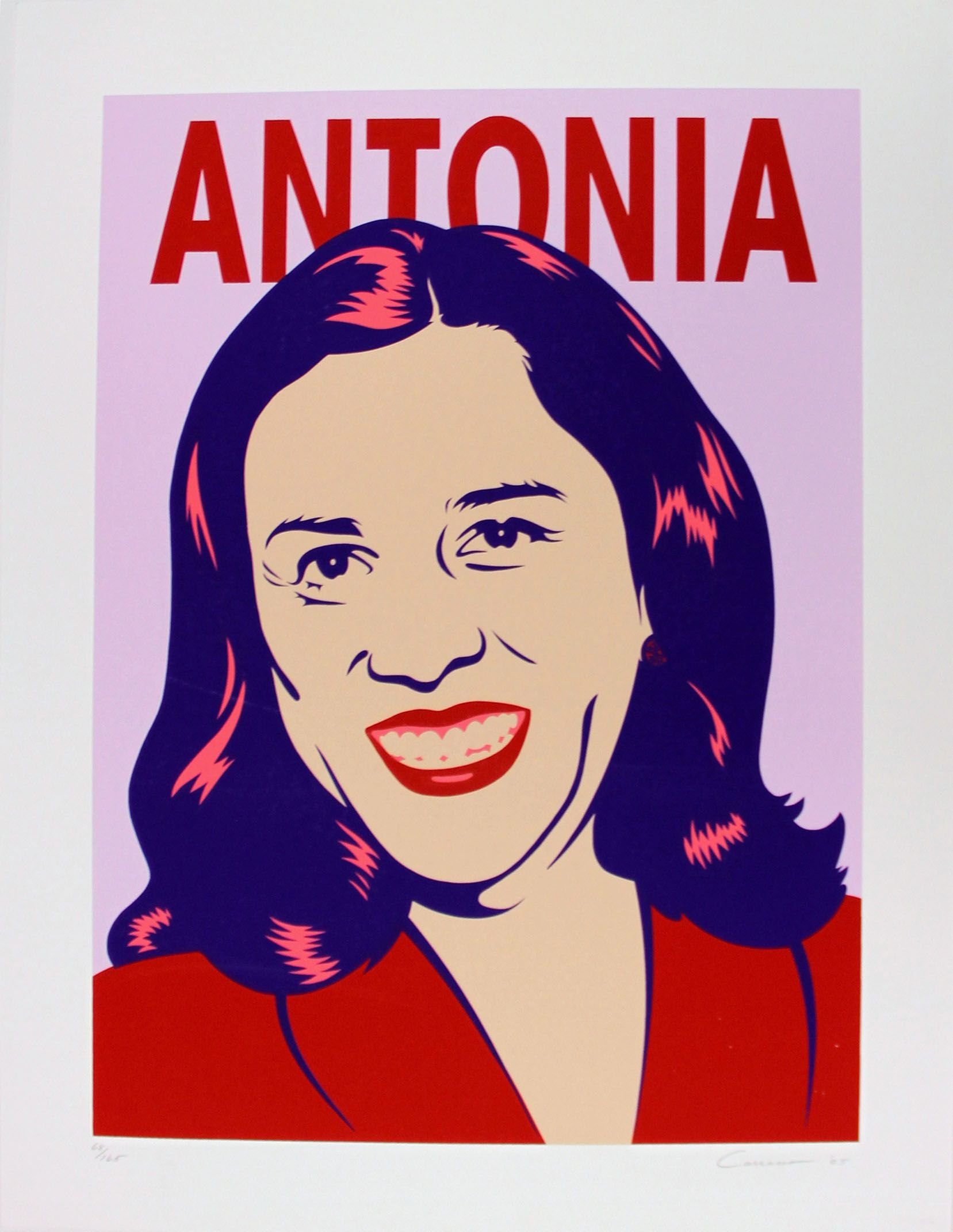

Antonia (2005), Barbara Carrasco

In this print, Carrasco presents a pop art style portrait of Chicana attorney, activist, and philanthropist Antonia Hernandez. She is most known for her role as plaintiff in the landmark federal class action lawsuit, Madrigal v. Quilligan, where Latina immigrant women were forcibly sterilized, either without informed consent or with coercion, at the Los Angeles County-USC Medical Center. Women of color and transgender folks, especially those in low income, predominantly migrant or first generation communities are most vulnerable to human rights violations including reproductive injustice. These folks cannot ultimately practice self-agency if state-sanctioned violence against them persists such as the threat to Roe v. Wade and the core needs of their communities remain unmet, despite their efforts to change these material conditions for themselves and future generations.

The Key (2002), Jerolyn Crute

Nacimiento (2004), Mita Cuaron

In this [Nacimiento] print, Cuaron depicts her first and only child swaddled in the protection of the Virgen's green mantle. She identifies the birth of her child and entry into motherhood as one of the most important moments in her life, extending gratitude to not only her child but birthers of new life everywhere. Reproductive justice is when parenthood is at the discretion of the individual who would be carrying and birthing the child, whether they decide to go forward with the birth or not. Agency should be affirmed as lying within the individual and factors of accessibility should not infringe upon one’s wishes for their body, family, and community.

Antonia (2005), Barbara Carrasco

The Key (2002), Jerolyn Crute

In this print, Crute addresses the housing crisis in Los Angeles, depicting a power struggle for a key between a city hall official, four adult community members, and a young girl. Capitalist interests of politicians and corporations take precedence over the well-being of families, family-owned businesses, and federally funded neighborhood resources. Gentrification threatens not only the efforts of housing activists and community members to sustain communities amidst displacement, but individual bodily autonomy. Housing is a human right that is inextricably linked to the well-being of children, whether it be physically or psychologically, making it necessary in conversations of reproductive justice. Poverty and experiences of houselessness resulting from conditions of poverty restrict access to healthcare, including reproductive screenings and treatment, in addition to increasing the margins at which folks are vulnerable to food insecurity, educational inequity, and sexual violence.

We All Count (2020), Martha Carrillo

In this print, Carrillo explores themes of resiliency and inclusion featuring her two close friends, Alice Bag and Shizu Saldamando, Shizu’s child, orange California poppy flowers, as well as a rainbow color scheme. She brings attention to census participation and its potential for making the needs of the vulnerable populations within our communities, such as infants, more greatly seen and heard. Census participation impacts accessibility to public services, which are especially crucial for newer generations. Similar to organizing efforts which center housing, census participation is presented as another action that can move us forward in our fight for reproductive justice.

Just as healthcare, education, and housing are central to reproductive justice, abolition of systems of oppression is equally important to reproductive justice. There is hope for an alternate framework of liberation. We can continue to use artistic expression as a vessel within our activism to achieve our goals of personal, community, and systemic transformation.

We All Count (2020), Martha Carrillo

Starlina Sanchez is the Summer 2022 Getty Documentation and Archives Intern at Self Help Graphics. & Art Sanchez is also a Mellon Mays fellow and recent graduate of Cal State University Fullerton, with a double major in Sociology and Women and Gender Studies.